What are medical textiles?

Medical textiles is one of the most important and continuously expanding fields in technical textiles. The scope of applications is vast and diverse, ranging from a single thread suture or simple cleaning wipes to complex composite structures for bone replacement and advanced barrier fabrics used in surgery rooms. Medical textiles utilise all major forms of textiles i.e. fibre, yarn, roving, woven fabrics, and nonwoven. Medical textiles can be grouped into four categories:

- Healthcare and hygiene products e.g. bedding, clothing, surgical gowns, cloths, wipes

- Extracorporeal devices e.g. artificial organs such as kidney, liver, or lungs, pacemakers

- Implantable materials e.g. sutures, vascular grafts, artificial ligaments, artificial joints

- Non-implantable materials e.g. wound dressings, bandages, plasters (Hasan and Anand 2014)

What is perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

Perfluorooctanoic acid, (also known as C8 or perfluorooctanoate) has been produced in industrial quantities for a wide array of uses since the 1940s; it is very persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (Wishart et al. 2018). PFOA and PFOA-related compounds belong to a group of fluorinated chemicals called per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), which are considered emerging pollutants of the 21st century (OECD). PFOA (a “forever chemical”) contaminates food, drinking water, land, and air. It also persists in the environment and in human bodies for years - exposure is linked to a considerable number of adverse health effects in humans, including increased cholesterol levels, thyroid disease, and cancers (EFSA 2018). The European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) recently set the provisional tolerable weekly intakes for PFOA at 6 nanograms per kilogram of body weight, lowering it from 1,500ng daily – an extreme reduction of 99.99% and a clear acknowledgement that these chemicals are much more damaging to human health than previously thought. A large portion of the EU population already exceeds these new safety levels.

The issue with PFOA

A number of regulatory initiatives have been taken due to concerns with PFOA. In 2006, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) launched a PFOA Stewardship Program, in which eight companies were invited to eliminate PFOA and its precursors by 2015 (US EPA). The Environmental Agency of Norway has amended its national consumer product regulation to ban PFOA from consumer products - this includes specific requirements for articles, textiles, and mixtures; the European Commission restricts the manufacture, marketing and use of PFOA. There is also the Madrid Statement on PFASs, signed by over 200 scientists concerned about PFASs being released to the environment, which includes actions for scientists, governments, chemical manufacturers, product manufacturers, purchasing organisations, retailers, and individual consumers (Blum et al. 2015). In 2017, a two-day workshop attended by more than 50 academic scientists and regulators took place in Zürich (Switzerland) to discuss PFASs (including PFOA). This international group made recommendations for cooperative actions and outlined how the science–policy interface regarding PFASs can be strengthened through new assessment and management approaches for highly persistent chemicals (Ritscher et al. 2018). More initiatives in different countries addressing PFOA (and other PFASs) can be found in the OECD publication, Risk reduction approaches for PFASs – A cross-country analysis (OECD 2015). Most recently (in May 2019), PFOA, its salts, and related compounds were listed under the Stockholm Convention.

In general, current alternatives to PFOA generally use:

- Shorter per- or poly- fluorinated carbon chains (≤6 carbons)

- Non-fluorine containing substances (such as siloxanes and silicone polymers)

- Non-chemical techniques (OECD 2013).

A recent study on the repellent properties of fluorinated short-chain and non-fluorinated durable water repellents (DWR) polymers in medical protective clothing concluded that sufficient repellency to polar liquids (like certain human body fluids) could not be achieved with current non-fluorinated DWRs, and that further innovation is needed (Schellenberger et al. 2019). For other textile properties, like water repellency, there are currently fluorine-free alternatives available already in use for some outdoor and sportswear textiles.

PFOA and alternatives to PFOA in medical textiles

Membranes used in certain medical textiles (e.g. in surgical gowns) can contain PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), a fluoropolymer that functions as a repellent, providing protection from blood and body fluids to reduce the risk of cross-infections for both patients and staff. Whilst PFOA has often been used as production aid in the manufacture of PTFE, leading global fluoropolymer manufacturers and progressive companies are now using alternative substances such as fluorinated polyether carboxylates. The United Nations expert evaluation has identified several potential PFOA alternatives for use in medical textiles such as short-chain fluorinated alternatives, non-fluorine containing alternatives, and non-chemical alternatives, including those that meet regulatory requirements and are currently in use (including some medical textiles). Following this evaluation, the UN expert committee did not recommend a specific exemption for PFOA use in medical textile membranes. Ignoring expert opinion, the European Union, however, successfully requested a five-year global exemption under Stockholm Convention listing, to continue using PFOA in medical textiles. No information has been provided by the EU to explain the need for this exemption.

Through strategic and sustainable procurement, the healthcare sector can surpass the restrained and unambitious policies and to demonstrate that substituting PFOA with safer alternatives is both feasible and viable.

The healthcare sector should minimise the risks posed by the toxic chemicals used in their procedures. HCWH Europe has conducted some provisional research into short-chain fluorinated alternatives (C6), non-fluorine containing alternatives, and non-chemical alternatives to PFOA used in medical textiles.

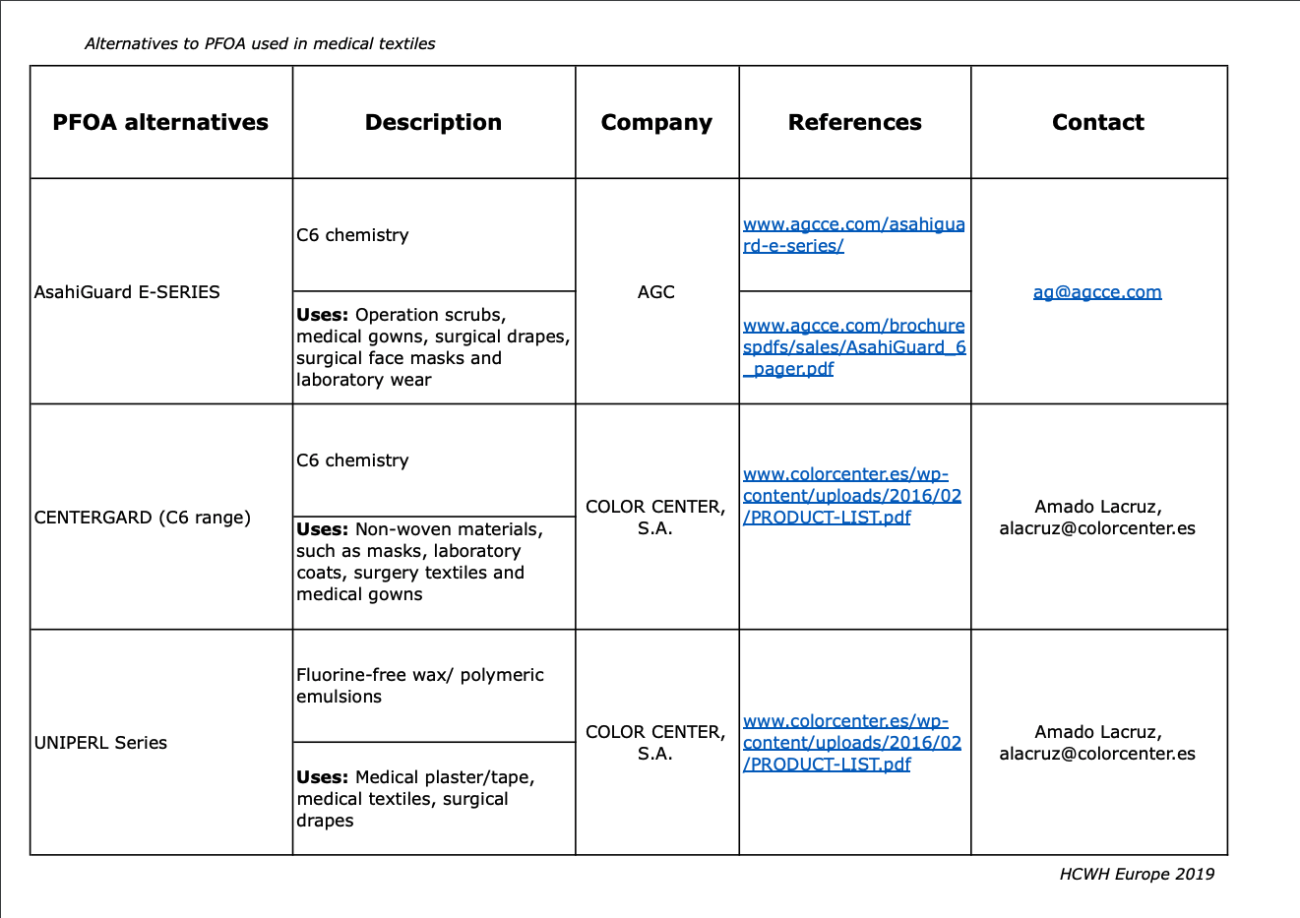

In the table below, information has been obtained from the websites of the companies and from e-mail/phone correspondence. All of the companies have locations in Europe except for GreenShield (USA) and Nicca Chemical Co. Ltd. (Japan). The applications listed below are not a complete list; medical textiles need to fulfil strict requirements and thus alternatives have to be first tested on the textiles to see if they are suitable. The information provided in this table clearly indicates that there are technically feasible alternatives to PFOA already available that meet regulatory requirements.

Through strategic and sustainable procurement, the healthcare sector can surpass the restrained and unambitious policies and demonstrate that substituting PFOA with safer alternatives is both feasible and viable.

Alternatives to PFOA used in medical textiles

Information obtained from the websites of the companies and from e-mail/phone correspondence.