The European Parliament has called on the Commission to urgently take all necessary action to ensure high level of protection of human health and the environment against endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) by effectively minimising overall exposure. This resolution, adopted in the parliament’s final plenary session with an overwhelming majority, asks the EC to treat EDCs in the same regard as carcinogenic or mutagenic substances. This comes in response to the European Commission’s communication on EDCs (November 2018) - widely criticised for failing to lay down specific actions.

This EP resolution is a powerful political message, outlining that there is “no valid reason to postpone effective regulation”, the parliament calls upon the Commission to develop a horizontal definition for EDCs based on the WHO definition and to produce concrete legislative proposals that remove EDCs from cosmetics, toys, and food packaging by June 2020. With this action, Members of Parliament have recognised that current regulations for man-made chemicals systematically underestimate the health risks associated with combined exposures to EDCs (or potential EDCs) and call on the Commission to take mixture effects and combined exposures into account in all relevant EU legislation.

As a member of the EDC-Free Europe coalition, HCWH Europe has long been calling on the EU Commission, Parliament, and Member State governments to update the 1999 European strategy on EDCs. Scientists and endocrinologists have also argued for decades that regulatory action has been too little, too late, and continue to advocate for stricter regulation of EDCs within the EU.

“The European Parliament has made a landmark statement and is showing that strong action against endocrine disrupting chemicals is an absolute priority. Now it is up to the European Commission to propose legislation to ensure that people’s health and our environment across Europe are protected against EDCs.” – EDC-Free Europe

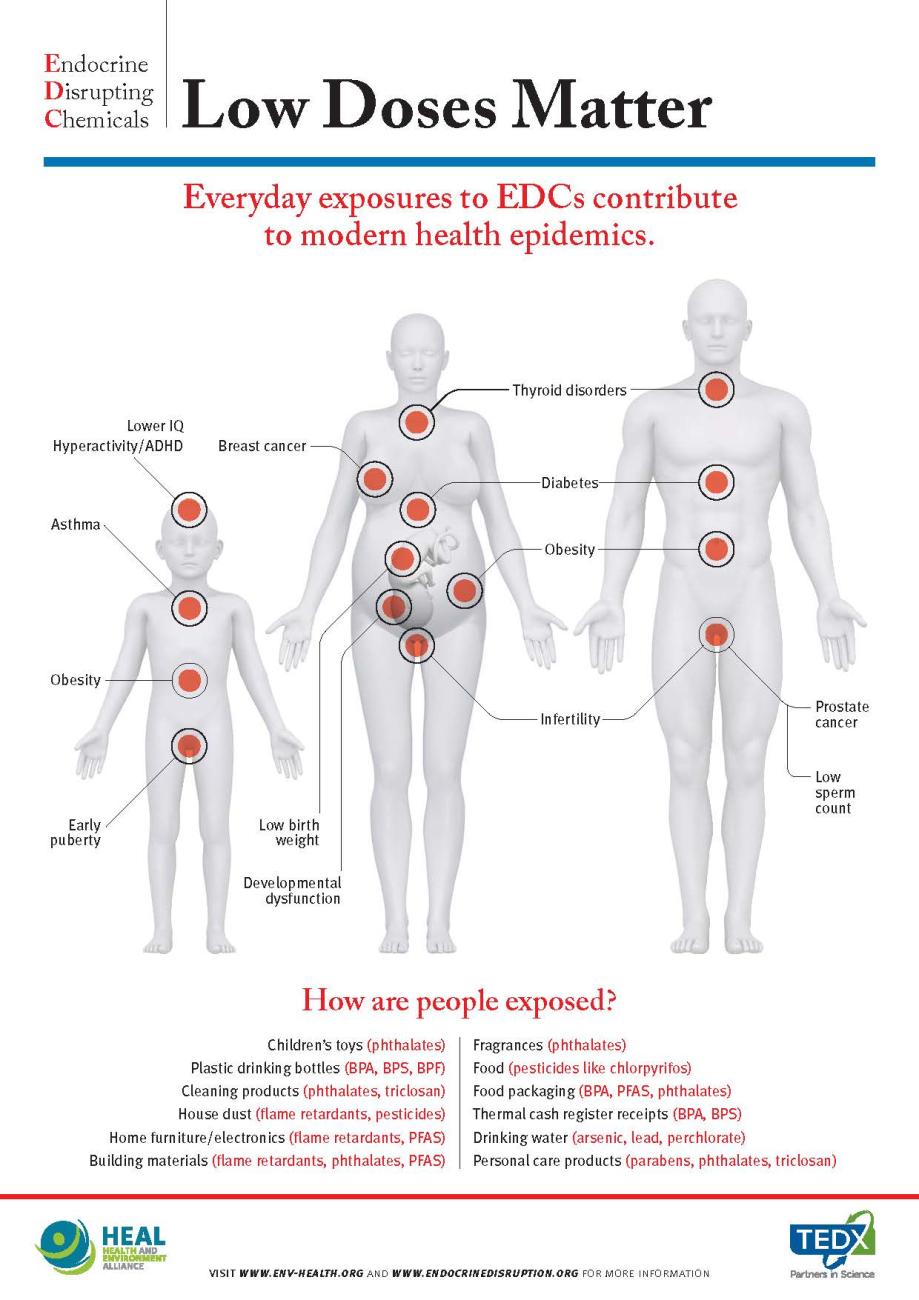

EDC-Free infographic: Low Doses Matter

Exposure to EDCs has been linked to serious health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, hormone-dependent cancers, reproductive disorders, neurodevelopmental disease, and intellectual impairment. The effects of these chemicals can have a continuing and re-occurring impact years later and even be passed on to the next generation.

Medical settings are another key area where humans are exposed to EDCs (such as certain phthalates and bisphenols) through direct releases into the human body through dialysis, blood transfusions, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for example. Medical devices made of PVC containing di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP, known EDC) present an important source of exposure to this reproductive and developmental toxicant for susceptible populations.

In the late 1960s, the first reports emerged documenting that DEHP can leach from plastic medical devices into body fluids and subsequently migrate into human tissues. Over 50 years after this discovery, regulatory communities are still struggling to define and manage potential human health risks posed by DEHP in medical devices.

The new Medical Devices Regulation (MDR; 2017/745 (EU)) permits EDCs in medical devices that come in contact with the body or with body fluids above a certain concentration (0.1% weight by weight) only when the manufacturer can justify their use with a risk-benefit analysis. Several steps must be considered for such justification, including possible alternative substances, materials, designs, and medical treatments. Preliminary versions of specific guidelines on the use of phthalates in certain medical devices have recently been prepared by the Commission Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks (SCHEER) and is currently open for public consultation (closing 29 April).

We hope that this opportunity to replace harmful chemicals (such as EDCs) with safer alternatives in medical devices will not be watered down during implementation of the MDR; there is extensive evidence that a DEHP and PVC phase-out is possible. Given the elevated risk of EDC exposure in intensive care settings; we must encourage rapid and widespread adoption of existing alternatives as well as development of new ones to improve patient safety. This will undoubtedly improve protection of the most vulnerable groups of EU citizens including neonates, infants, the elderly or the critically ill, as well as pregnant or breastfeeding women.